In Sri Lanka, children are forced to throw their dreams to the wayside

Youth Skills in South Asia

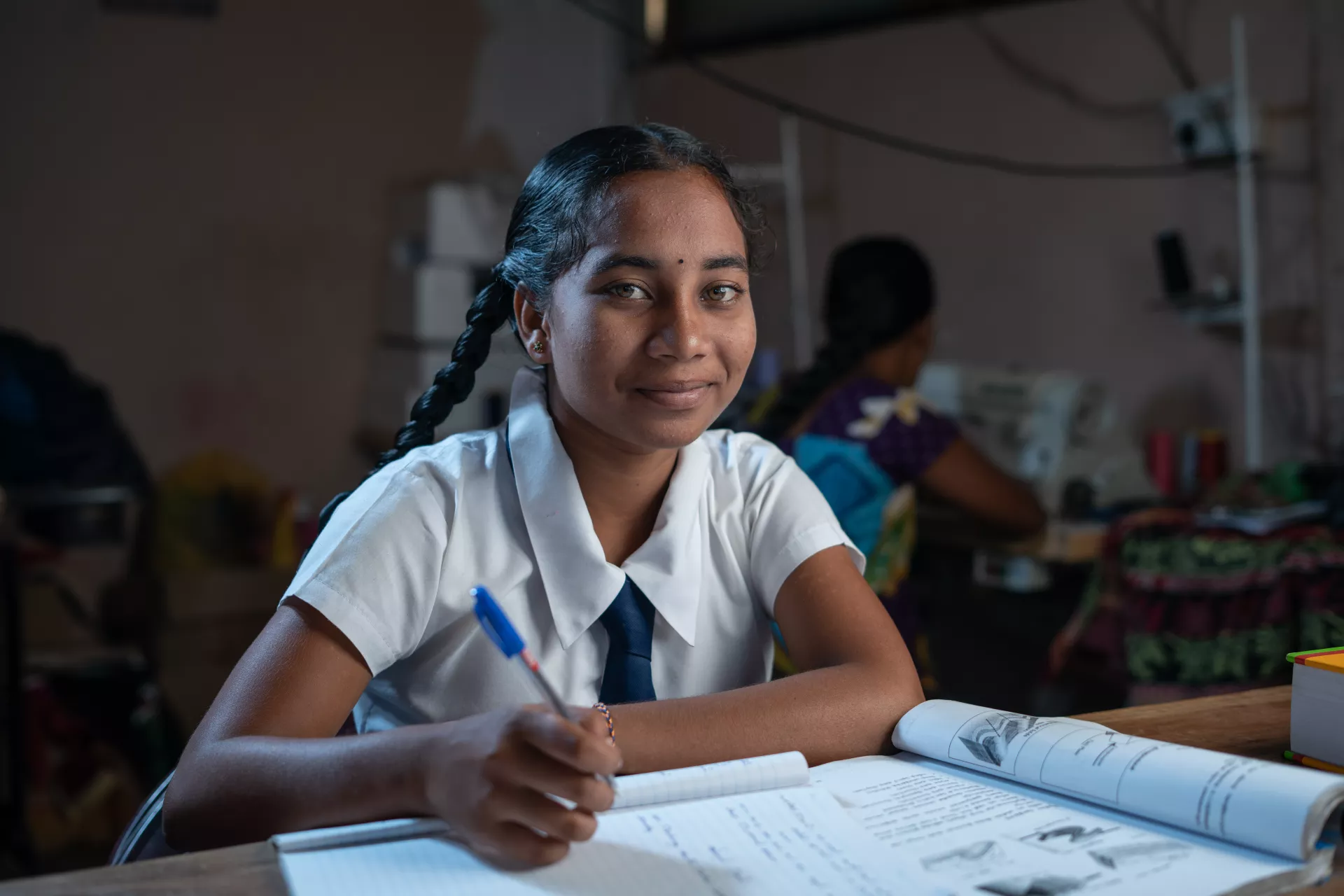

Sampoor Resettlement Area, Trincomalee, Sri Lanka – Yathusia and her father were home when he died. He was caught in the crossfire of Sri Lanka’s civil war – and Yathusia was there to see it all.

“There was shooting outside, and a bullet fired into the house and killed him,” Yathusia said. “There was fighting everywhere. Our houses were joined, and lots of people lived next door, but I didn’t feel safe or protected. There was constant fear of the conflict.”

The next few years were no easier. Shattered, Yathusia’s mother brought her family to a camp for internally displaced persons in the north of the country. It was supposed to be a place of sanctuary, though in reality, it was anything but.

“There was a lack of resources, and safety and security were an issue,” Yathusia said. “Along with finding enough food and water.”

Another big issue was education – or rather, the lack thereof. Yathusia’s lifelong dream was to become a lawyer, but even before going to the camp, her school was less than basic.

“There were few facilities, no blackboards, no walls to display things on,” Yathusia said. “We learned under a tree within a very temporary structure. Learning wasn’t very organized.

Once the family was displaced, Yathusia’s educational experience got worse. After a year of living in the camp in northern Sri Lanka, the family moved to another camp in the east. At this camp, there was not a single school for Yathusia and her siblings to attend, nor an alternative learning centre they could use as a substitute.

“In the camp, we lived in a hut,” Yathusia’s mother said. “A tin shed was our house, and every house in the camp was adjoining. Next door to us was one tin shed, and next door to them was another, and another after that. Families that didn’t have children often played music loudly and disturbed us, so it was hard to focus on things like learning and education.”

Anxious about losing her chance to become a lawyer, Yathusia tried to study regardless of the circumstances.

“It was hard to pursue an education in the way that I wanted because I had to take a national exam while I was still inside the camp,” Yathusia said. “That posed a lot of challenges."

"As a displaced person, I have been scattered here and there. I have lived like this for nine years.”

A new start brings new challenges

After four years and two camps, Yathusia and her family resettled in Sampoor. Their home is close to the school, and there are a water pump and a gas tank within walking distance of the house. Even so, Yathusia has continued to face insurmountable challenges.

“After we came here, I enrolled in a nearby school,” Yathusia said. “It was the third time I had done that in one year, and I had to try hard. There was limited access to additional support, and at first, my grades were quite low. I had to work hard to ensure my level of education was secure. I did a lot of papers and took additional classes, and my mother used to wake me up early in the morning to study.”

Eventually, Yathusia’s grades started to climb. Recently, she achieved seven A’s and B’s, along with a scholarship of one thousand rupees ($14) for her scores in mathematics. Unfortunately, however, none of those grades were in subjects Yathusia wanted to study.

“I was interested in the science stream, but since we didn’t have those subjects at school, I had to follow the arts stream instead,” Yathusia said. “Normally, following the arts stream makes it hard to get a job once you’ve graduated. Those who follow a science stream are employed quickly."

"I would really love to learn and study law, but the subjects that are available to me are not suited to my aspirations.”

Some students travel to a town near Sampoor to take science classes, but Yathusia – and many others – cannot because of fees and transportation costs.

“I feel sad that I cannot study law, but what can I do?” Yathusia said. “My mother is pushing me to study in town, but I don’t want her to continue suffering for me. With the subjects I’ve taken, I hope, at least, to secure a college education. Many other children have achieved seven, six or five passes in my school. They are passionate about science but are only able to take the arts stream. If we get good passes, we can, at least, go to the College of Education and study for a diploma course. Once we’ve graduated, we’ll have a better chance of securing a job.”

Faced with a lack of relevant classes, Yathusia has been forced to shift her goals.

“I still want to be a lawyer, but my subjects just aren’t relevant,” Yathusia said. “I need logic and political science to become a lawyer, but I can’t take those. My plan now is to be a teacher in a secondary school.”

A call for change, opportunity and education

Yathusia’s childhood dream has been crushed. But still, she is pushing forward. Every morning, she wakes up early to study; every evening, she attends additional night classes to catch up. In her spare time, Yathusia helps with household chores and supports her mother’s small business.

“Whenever I find the time, I help my mother,” Yathusia said. “My mother is everything to me. She has provided me with books and fulfilled any needs I might have. I depend on my mother’s earnings from her jobs to get school supplies.”

Despite their challenges, Yathusia’s mother is rebuilding her family’s life. Even though Yathusia is still a child, she is determined to help.

“I want to have a career because I want to look after my family,” Yathusia said. “My mother has suffered a lot for me, and I want to secure an education for my brothers. In five years, I see myself working. When school is out of term, I’ll take extra classes during the holidays in subjects like computing. I’ll help my mother and support our family.”

Still, Yathusia urges the Sri Lankan education system to change – if not for her, then for the millions of children to come.

“What I want most is for my school to have more subjects so everyone can follow their desired career path,” Yathusia said. “That would change the lives of all the children in our community. I worry that I can’t take the science stream or commerce, but that worry isn’t really for me. My plea is for the students studying below me, and the children who have yet to start school. The younger generations should have the opportunity to study whatever they like.”