How an adolescent girl helped her community fight COVID-19

Studying at non-formal basic education centers established by UNICEF with funding from Government of Japan and support from Sindh’s authorities empowers girls to become agents of change in their communities

GHOTKI, Pakistan, 18 March 2022 - “People tend to fear new things and to resist change,” says 15-year-old Firdous Bhutto, who lives in Bhutta Mohalla, a densely populated community in Qadirpur village in the Ghotki District of Pakistan’s south-eastern Sindh province.

“Initially, people in my community refused to adhere to key preventive behaviours against COVID-19. Later, they refused to be vaccinated against the virus,” the student tells.

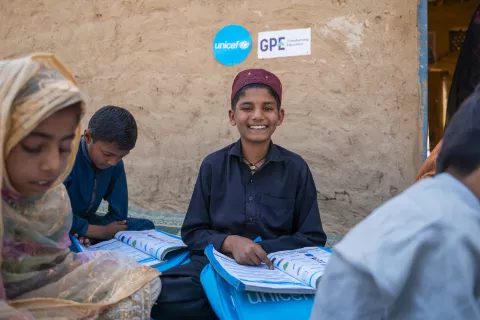

About 150 families live in Bhutta Mohalla, with most men working in agriculture or construction. Firdous is one of only 30 students aged 12 to 16 who study at a Non-Formal Basic Education (NFBE) Centre established by UNICEF with support from Sindh’s Directorate of Literacy and Non-Formal Education and funding from the Government of Japan in collaboration with Japan’s International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in Pakistan.

Located in the midst of a maze of narrow muddy roads and open drains, the one-room center is a beacon of hope and the only learning facility in this impoverished community.

The adolescent girls and boys studying at the NFBE Centre, whose teacher Habibullah happens to be Firdous’ paternal uncle, have always taken a keen interest in the health and hygiene sessions which are included in the curriculum. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly across the world early 2020, the social organizers leading these sessions started to mention COVID-19 standard operating procedures (SOPs).

As the eldest of her six siblings, three of whom study with her, Firdous taught her family what she had learnt as soon as she came back home. Soon, she decided to spread the information further.

“No one is safe until everyone is safe. Extraordinary circumstances require extraordinary actions. After my school shut down because of the lockdowns, I went door to door and told other families about COVID-19,” the student explains.

Convincing the villagers of adhering to COVID-19 key preventive behaviours was an uphill task. Initially, people dismissed the information she shared, but Firdous was not discouraged.

After word spread that people living in villages around had become severely ill due to the virus, people started to pay heed to what she said.

“No one is safe until everyone is safe. Extraordinary circumstances require extraordinary actions. After my school shut down because of the lockdowns, I went door to door and told other families about COVID-19”

After several months of closures, schools in Pakistan started reopening sporadically. Firdous’ uncle and teacher Habibullah attended a UNICEF-supported training on safe reopening of schools, where he learnt how to resume teaching while keeping the students safe at school. When the NFBE center reopened, Firdous assisted him to ensure that all the students adhered to COVID-19 SOPs.

Firdous first heard about the COVID-19 vaccine in March 2021 from an elderly maternal uncle who lives in Kashmore, a city in Northern Sindh. As he visited her family, he told her that he had just been vaccinated.

“COVID-19 was overwhelming for all of us. I was incredibly relieved to hear about the vaccine. It gave me hope that the pandemic may soon come to an end,” Firdous explains.

Pakistan’s national COVID-19 vaccination drive, led by the federal Government and provincial authorities with support from UNICEF, initially targeted only seniors. Once more, Firdous went door to door, this time to try and convince older members in her community to get the jab. She visited several families every day, only to be turned back as she faced stiff resistance from everyone.

Misinformation regarding the COVID-19 vaccine was rampant on social media. Both community elders and younger people were very skeptical. Fake rumours of COVID-19 vaccines causing death and other weird conspiracy theories were doing the rounds in the village. Some people even began scolding Firdous, trying to deter her from promoting vaccination.

“My community’s response to the vaccine was very disheartening. I tried to explain that just like the polio vaccine, the COVID-19 vaccine was beneficial and harmless, but to no avail,” she tells.

Firdous decided to focus instead on her immediate family. As her paternal aunt Zebunnisa was eligible for vaccination, Firdous tried to convince her to get vaccinated. To alleviate her fears, she arranged a call with her fully vaccinated uncle in Kashmore. The effort paid off and Zebunnisa got vaccinated against COVID-19 the very next day. This prompted other members of the community to gradually follow in her footsteps.

“My community’s response to the vaccine was very disheartening. I tried to explain that just like the polio vaccine, the COVID-19 vaccine was beneficial and harmless, but to no avail”

Over the months, the Government lowered the age of people who were eligible to vaccination.

“I was so excited when it was finally announced that everyone aged 12 and above can get vaccinated!” Firdous tells. “I was the first adolescent to get vaccinated in my community, I got the jab as soon as a vaccination team visited our neighbourhood. I gathered my friends and got them vaccinated too!”

Thanks to Firdous’ efforts, all the students at the NFBE center have now received at least their first shot of COVID-19 vaccine.

Firdous’s father Nasrullah Bhutto, a farmer who only studied until eight grade himself, often jokes that it is impossible to say no to his daughter because she never gives up.

“The education which Firdous has received at the centre has empowered her to speak up and advocate for what is right. She has become a role model despite her young age,” he tells.

Nasrullah says that he realized the value of education when he was hired at a factory owned by a foreign company in Karachi.

“I was the only one among 50 coworkers who had not graduated from high school. When my contract expired, it was not renewed, while some of my coworkers got better contracts,” he tells. “When I went back home, I told my wife that our children would study and should never have to face the embarrassment I face in society.”

Nasrullah immediately enrolled Firdous and her siblings in a school located in the community at the time, but which taught only up to grade 3. As traveling out of the neighbourhood to study was not considered safe, Firdous and her siblings had to drop out after third grade. They resumed studying only after UNICEF opened an NFBE Centre in Bhutta Mohalla with funding from Government of Japan and support from Sindh’s Directorate of Literacy and Non-Formal Education.

“The NFBE Centre model thrives on community support. The teachers belong to the communities where they teach, which helps convince parents to enroll children, especially girls. We try to foster a sense of ownership within the community so we can achieve sustainable and long-lasting results,” says Rehana Batool, UNICEF Education Officer in Sindh.

So far, 150 NFBE Centres have been established by UNICEF under the “Enhancement of Non- Formal Education” project funded by the Government of Japan in collaboration with JICA and with support from Sindh’s Directorate of Literacy and Non-Formal Education across the province.